The Salome Dancer: The Life and Times of Maud Allan

PDF scans

Salome Dancer_Cherniavsky, p. 83-84 Maud as Salome, cult icon of the Decadents

Salome Dancer_Cherniavsky, p. 134-140 Family disaproval

Salome Dancer_Cherniavsky, p. 141-142 Salome as femme fatale, in church and in art

Salome Dancer_Cherniavsky. p. 143-148 Courage, wit and Count Zichy’s cruel joke

Salome Dancer_Cherniavsky. p. 167-168 Church disapproval of dancing and biblical figures on stage

Salome Dancer_Cherniavsky, p. 174-175 Maud’s influence on fashion and society

Author: Felix Cherniavsky

Title: The Salome Dancer: The Life and Times of Maud Allan

Form: biography

Published: 1991

Location: Canada

Reflections

Maud Allan (1873-1956) was born in Toronto, educated in San Francisco and then Germany as a classical pianist, and eventually became known as a dancer in London before conquering the rest of Europe.

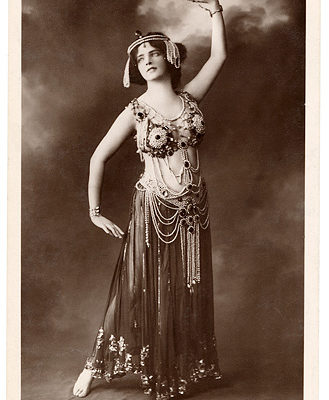

She was an innovator of impulse-based modern dance during an era of extreme social constraint in North America and Western Europe. She slipped out of her corsets and petticoats to dance barefoot and barely clad on public and private stages.

She expressed intense emotions from joy to devastation. She was comfortable in her body. She pursued her unique art in spite of known detriments to her social standing and personal life. She channeled her own life tragedy into her art in front of world audiences.

She was warned by her mother and by family friends that pursuing dance would make her unsuitable for marriage, and would bring upon her the low status that dancers held.

She enjoyed success throughout Europe and was hailed for her musicality and thorough commitment to her expressive art. She caused scandal for her immodest costumes, which aided her fame. She danced to a variety of orchestral music, but was best known for her Vision of Salome, which was usually the finale of her shows.

If Salome holds our fascination for her unveiled emotions – desire, ambition, seduction, enjoyment of her physical state, then Maud personified those same qualities. The details of her family’s history were kept veiled from her European associations. Her brother, Theo, had been hanged in San Francisco for the murder of two women. Maud changed her name and avoided mention of this event to most of her acquaintances. In this way, she lived a mystery. Salome’s mystery was her power to seduce the powerful, and in later retellings, her attraction to John the Baptist. Maud was publicly unveiled in the passion she felt for music, the stories that each piece held for her, and her profound feelings of both elation and tragic mortality.

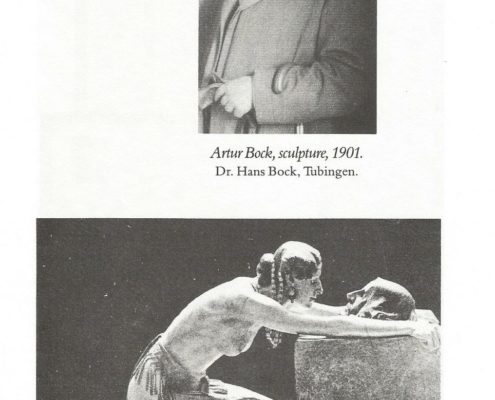

(141-142) The Vision presented Salome as a femme fatale and as decadence incarnate. Both views were modern. For centuries Salome had been approved by the Church and was a popular subject for artists in many disciplines. The traditional view, carefully nurtured by the anti-feminist policies of the Church, was simply that she was an evil woman responsible for John the Baptiste’s death. In the mid-nineteenth century, however, artists began to view her as the archetypical femme fatale. Herinrich Heine, Gustave Flaubert, and, a generation later, Oscar Wilde, wove elaborate fantasies around her, and in so doing removed her from traditional associations.

(142) All these nineteenth-century artists focused on Salome’s sensuality, perverseness, and seductive powers. By the end of the century she also personified the decadence of an old society on the brink of radical reform or dissolution.

The Decadent movement reflected fascination with darkness, indulgence, excess, ennui, sensuality, artificiality, subverted sexuality and morbidity.

(83-84) For Richard Wagner and Charles Baudelaire, two of the progenitors of the Decadent movement, an ennui so deep-rooted as to be more a disgust than a tiredness with life led them beyond the conventions of social behaviour and creative expression. The affinity of Maud’s art with the Decadent movement, which flourished throughout the last third of the nineteenth century, is very clear. Much of her sensational success lay in her daring projection of such feelings, from her unique portrayal of Salome (already a cult figure for the Decadents) to her intensely personal version of Salome’s story. It may be argued that, although the Decadent movement culminated sociologically in Oscar Wilde’s downfall, its last aesthetic expression was Maud’s forgotten Vision of Salome.